Good for Girls

Good For Girls, Good For Life

Discover the transformative Good for Girls, Good for Life program of work, a groundbreaking initiative by Hunter New England Population Health and the University of Newcastle.

Our dynamic team, feature top researchers in physical activity, implementation science, and community and school-based programs. We collaborate with health, education experts and listen to the voices of women and girls to design, implement, and evaluate innovative, scalable, and cost-effective solutions to increasing girls’ opportunities to lead an active lifestyle.

We envision and advocate for a world where every girl feels safe, supported, and motivated to engage in physical education, activity, and sports, free from gender discrimination.

Why physical activity?

Regular physical activity is essential for the healthy development of children and teenagers. It strengthens their bones, supports muscle growth, and promotes overall healthy development.[1]

Staying active also helps improve motor skills and boosts brain development, setting the stage for better learning and cognitive growth. The healthy habits formed during childhood often continue into adulthood, laying the foundation for a lifetime of well-being.[1-3]

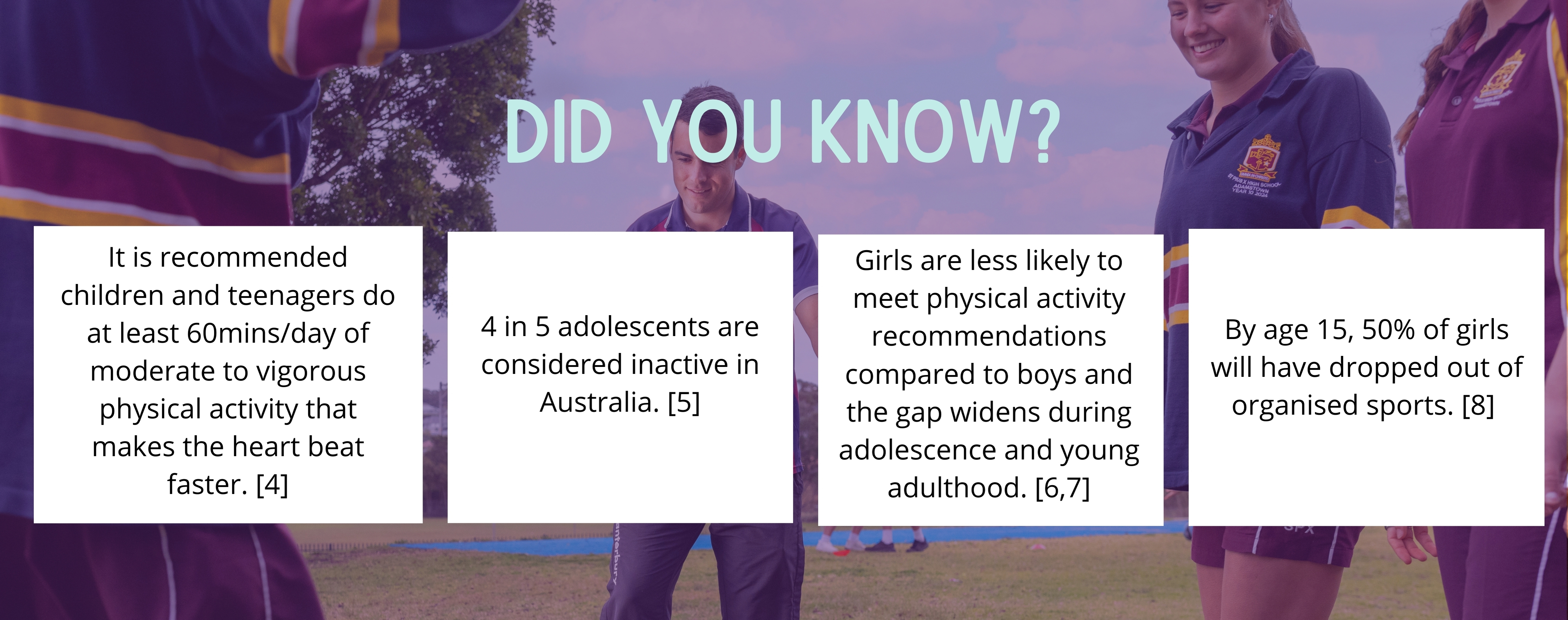

[4-8]

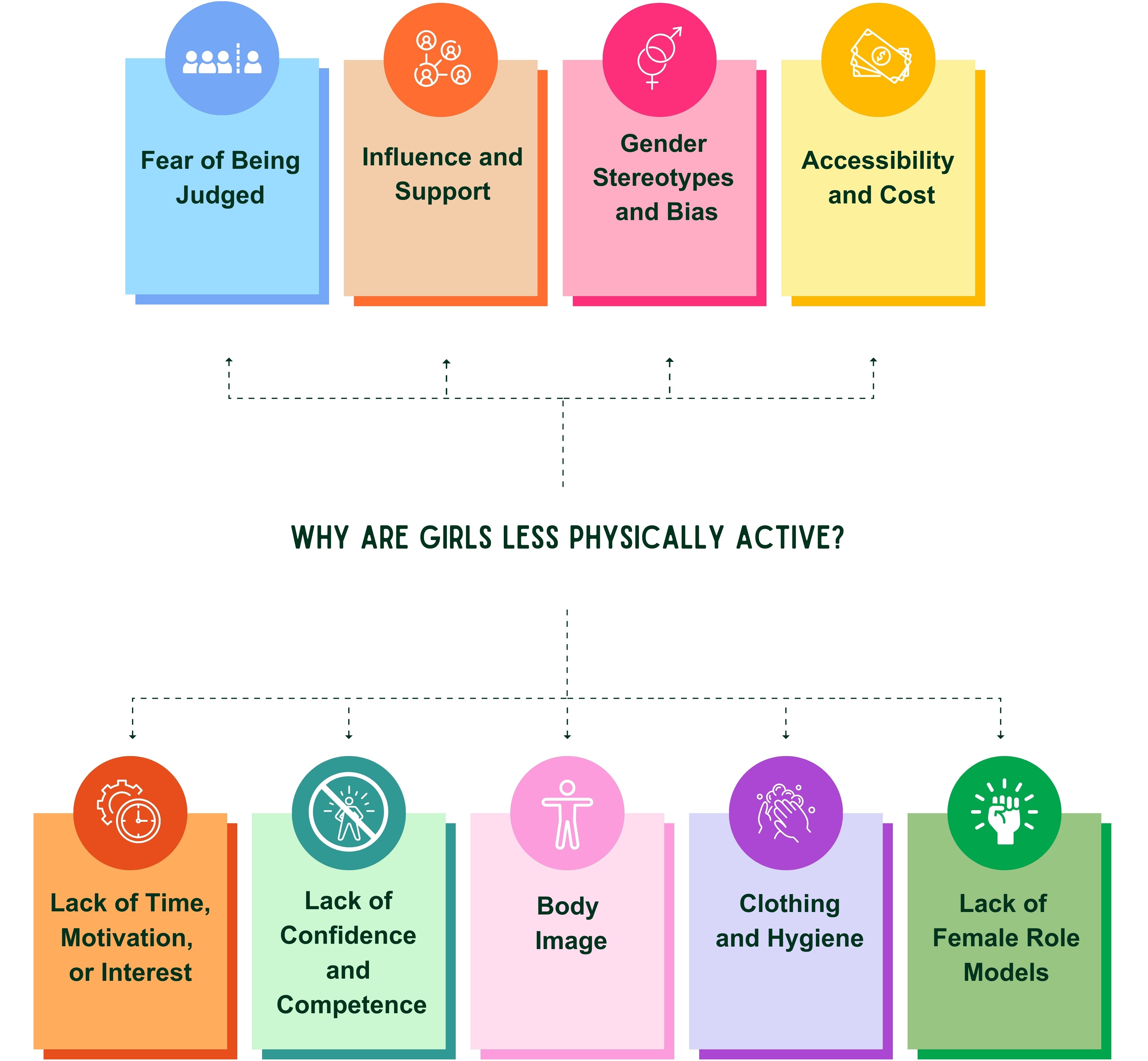

Barriers to girls being active

While physical activity is vital for girls' health and well-being, numerous barriers limit their participation. These challenges often stem from social, environmental, and cultural factors, including traditional gender expectations, inadequate access to safe and supportive spaces, and restrictive school uniform policies. Addressing these barriers is essential to empowering girls to engage in regular physical activity.[9-20]

Fear of negative evaluation from others based on physical abilities, appearance, or choices of activity.

The presence or absence of encouragement and support from family, peers, and mentors significantly impacts a girls’ decision to engage in physical activity.

Gender bias and stereotypes can create barriers that discourage girls from engaging in sports by reinforcing societal norms that label such activities as inappropriate or unfeminine.

Limited access to safe and affordable facilities, equipment, and programs, particularly for girls from low-income backgrounds or rural areas.

Busy schedules, competing priorities, and a lack of motivation or interest can prevent girls from prioritising physical activity in their lives.

Self-doubt about one’s abilities and their competence to willingly participate in sport skills and physical activities.

Concerns about body image, including perceptions of attractiveness and body weight, as well as practical issues like menstruation, can deter girls from participating in physical activities.

Practical considerations such as suitable clothing for physical activity, access to changing facilities, and time constraints for showering afterward can affect girls' ability to participate comfortably.

Inspiring female role models who showcase diverse pathways in sports are crucial for inspiring girls to engage in physical activities.

Alignment of Good for Girls, Good for Life with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

Goals: Good for Girls, Good for Life is committed to advancing universal well-being by bridging gender gaps and promoting equality through quality education and evidence-based, cost-effective, and scalable interventions to improve the health and well-being of children and teenagers.

Actions: Our team is actively researching ways to reduce barriers to girls' participation in physical activities, such as advocating for activity-enabling school uniforms that promote movement and creating dedicated spaces during school breaks to foster inclusive environments where all students can thrive.

Measures: We rigorously evaluate the outcomes of our projects using robust, evidence-based methods. Our approach includes longitudinal studies, randomised controlled trials, and comprehensive data analysis to ensure that our interventions are not only effective but also sustainable. By systematically measuring impact, we contribute to the achievement of the SDGs, particularly Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being), Goal 4 (Quality Education), and Goal 5 (Gender Equality). Our focus on scalability ensures that successful interventions can be widely adopted, maximizing their positive impact on children's and teenagers' lives globally.

[21]

[1] Archer T. Health Benefits of Physical Exercise for Children and Adolescents. Journal of Novel Physiotherapies. 2014;04.

[2] Rasmussen M, Laumann K. The academic and psychological benefits of exercise in healthy children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2013;28(3):945-62.

[3] Diamond AB. The Cognitive Benefits of Exercise in Youth. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine. 2016;1(16).

[4] Team ME. 50% of Australian teenage girls quit sport by 17, suncorp report reveals Australia: Ministry of Sport; 2019 [updated 2019; cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/RefLink123

[5] Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, van Sluijs EM, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children's accelerometry database (ICAD). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113.

[6] Kretschmer L, Salali GD, Andersen LB, Hallal PC, Northstone K, Sardinha LB, et al. Gender differences in the distribution of children’s physical activity: evidence from nine countries. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2023;20(1):103.

[7] Organisation WH. Physical activity: World Health Oragnisation; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity.

[8] Care AGDoHaA. Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians Australia: Australian Government; 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians/for-children-and-young-people-5-to-17-years.

[9]Mitchell G. Selecting the best theory to implement planned change. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2013;20(1):32-7.

[10] Allison R, Bird EL, McClean S. Is Team Sport the Key to Getting Everybody Active, Every Day? A Systematic Review of Physical Activity Interventions Aimed at Increasing Girls' Participation in Team Sport. AIMS Public Health. 2017;4(2):202-20.

[11] Biddle SJH, Whitehead, SH, O'Donovan, T, Nevill, M. E. Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: A systematic review of recent literature. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005;2:1543-5476.

[12] Duffey K, Barbosa A, Whiting S, Mendes R, Yordi Aguirre I, Tcymbal A, et al. Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity Participation in Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Front Public Health. 2021;9:743935.

[13] Laird Y, Fawkner S, Kelly P, McNamee L, Niven A. The role of social support on physical activity behaviour in adolescent girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016;13.

[14] Eime RM, Charity MJ, Harvey JT, Payne WR. Participation in sport and physical activity: associations with socio-economic status and geographical remoteness. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:434.

[15] Watson A, Eliott J, Mehta K. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity during the school lunch break for girls aged 12–13 years. European Physical Education Review. 2015;21(2):257-71.

[16] Cowley E, Olenick A, McNulty K, Ross E. “Invisible Sportswomen”: The Sex Data Gap in Sport and Exercise Science Research. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal. 2021;29:1-6.

[17] Standiford Brown A. Promoting physical activity amongst adolescent girls. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2009;32(2):49-64.

[18] Pearson N, Braithwaite R, Biddle SJH. The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Physical Activity Among Adolescent Girls: A Meta-analysis. Academic Pediatrics. 2015;15(1):9-18.

[19] Corr M, McSharry J, Murtagh EM. Adolescent Girls' Perceptions of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(5):806-19.

[20] Standiford A. The Secret Struggle of the Active Girl: A Qualitative Synthesis of Interpersonal Factors That Influence Physical Activity in Adolescent Girls. Health Care for Women International. 2013;34(10):860-77.

[21] Nations U. The 17 goals United Nations: United Nations; 2024 [updated 2024; cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.